Unsettling times: Bat Ayin adjusts after resident’s murder

While those who knew Erez Levanon say their faith in God and Israel remains strong, the incident’s portrayal in the media has struck a raw nerve.

click here for original posting

By Amihai Zippor

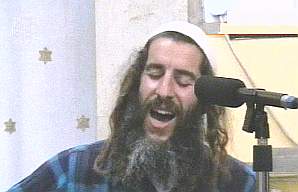

The close-knit Gush Etzion community of Bat Ayin was shocked when the body of musician Erez Levanon was discovered late Sunday night, February 25, in a nearby ravine. A pious and quiet father of three, Levanon, 42, was also a teacher of Torah and a Bratslaver hassid who would often go to the adjacent forest to meditate and pray. Two Palestinian teenagers from the nearby village of Safa were arrested the following day and confessed to stabbing Levanon in a politically motivated act. While those who knew him say their faith in God and Israel remains strong, the incident’s portrayal in the media struck a raw nerve.

“It needs to be understood that Erez was just a person who was killed for going out into the forest to meditate and commune with God. He wasn’t carrying a weapon and wasn’t there to provoke anyone,” says Avi Neuman, a student at the Bat Ayin Yeshiva whose student body mainly consists of North Americans. “He was there to live a life and I think it’s important for people to know he was a person, not a ‘settler’ killed in some valley ‘north of Hebron’ and not a symbol of this or that from either side. He was a father and a husband, and people have to remember that.”

Like many others, Neuman’s wife Debby explains the entire episode as a shock but “not because we are settlers.” “These are people who love the land and want to sense they can feel comfortable in the land,” she says. “The only difference,” she adds, “is that they are trying to forge a deep spiritual, physical and religious connection with it as a living land. So in that way it’s certainly harder when something like this happens, because it’s the opposite of what people think.” Those “people” she directed her thoughts toward are the many Israelis who look upon the settlers as an obstacle to peace or as fanatics “stealing Arab land,” a claim many members of the community say is not only incorrect but an image that has to change.

“For the entire world, including much of the Hebrew press, the headline for Erez’s murder was that a settler had been killed,” says Daniel Winston, a psychologist and a seven-year resident of Bat Ayin. “The implication was that he wasn’t just a Jew, but a settler, and that in some way, from the perspective of the people who feel we shouldn’t be here, it suddenly justified his murder.” Explaining that he believes in “the democratic and Jewish principle that there is no such thing as guilt by association,” it angers him that “in the eyes of many observers once a settler does anything, he’s not doing it as an individual but as a settler.” “How can anyone take the actions of an individual and besmirch the moral fiber of that individual’s entire neighborhood?” he asks. Winston suggests that in the same way that other minorities are put down, the Israeli left’s label of “settlers” for people who live in Judea and Samaria and their use of it in a derogatory fashion is no different than attitudes toward other groups that are harassed. “They have a complete double standard when it comes to allowing a deprecating attitude toward settlers, based entirely on a huge body of misinformation and in many cases calculated lies of who we are, what we believe and what we do,” he says.

Bat Ayin is one of the only Jewish communities in Judea and Samaria without a fence around it. Although this event has highlighted the dangers and called into question the security arrangements of the community, the policy is not expected to change. Rabbi Natan Greenberg, head of the Bat Ayin Yeshiva, explains that the “No Fence” philosophy has two components. Referring to the description given in the Torah of the Israelites who scouted out the land and returned to the people in the desert with a harrowing report that the inhabitants’ cities were strong, fenced in and walled, Greenberg cited the biblical commentator Rashi as his proof that “a security fence is not necessarily helpful or effective.”

“Rashi points out that they misread what they saw. What they should have understood was that the people in the land were cowardly, fearful and afraid; instead they deduced the opposite,” he says. The second component, says Greenberg, is more ideological. “The Jews didn’t come back to [the Land of Israel] with all its historical significance to be living fenced in on a reservation. “We are in the land. We are of the land. We are not unaware of the potential threats of the security situation, but if everything was defined by the level of security logic, then I’m not sure there’s a lot of logic for Jews to be in Israel as opposed to America or Canada.”

Bat Ayin is also near to the proposed route of the security barrier the government is building. Although the Gush Etzion bloc is considered to be relatively safe and lies on the Israeli side of the barrier, some Bat Ayin residents are concerned that the security situation will deteriorate further if it is built nearby. “All of the active security authorities who know this region agree that it is patently insane to put the fence right up against a yishuv [settlement],” says Winston, who is confident residents will continue to travel freely in the area.

Although the Neumans are living in Bat Ayin temporarily until Avi finishes his studies, there is one thing they agree on. “We’re here at this moment because this is the only spot on Earth where we can grow in the ways we need to grow right now and do what we’re supposed to do in the world,” Neuman says. “Something like this is hard, so maybe you have to make practical adjustments, but more than anything it’s really a test of faith and you ask yourself important questions.” As for the future, one of the most difficult questions he is facing is how to view his Arab neighbors. “Right now, part of what this did to me is that I have to figure out if we speak the same language.”